My Visit to Bainbridge Island

Japanese American Exclusion Memorial

Bainbridge Island is beautiful, located on the Puget Sound within a ferry’s distance from Seattle. In the 1880s, Japanese immigrated to the west coast of America, some coming to work at Bainbridge’s Port Blakely Sawmill. Though this sawmill grew to be one of the largest in the country, the poor working conditions and lack of advancement for the Japanese workers caused many to leave the sawmill to start their own businesses. By the 1920s, the communities of Nagaya and Yama had Japanese American owned enterprises that included farms, grocery stores, gardens and nurseries, a noodle shop, tofu maker, traditional bathhouses, Japanese language school, a Baptist Church and Buddhist Temple in a community of several hundred residents of Japanese heritage.

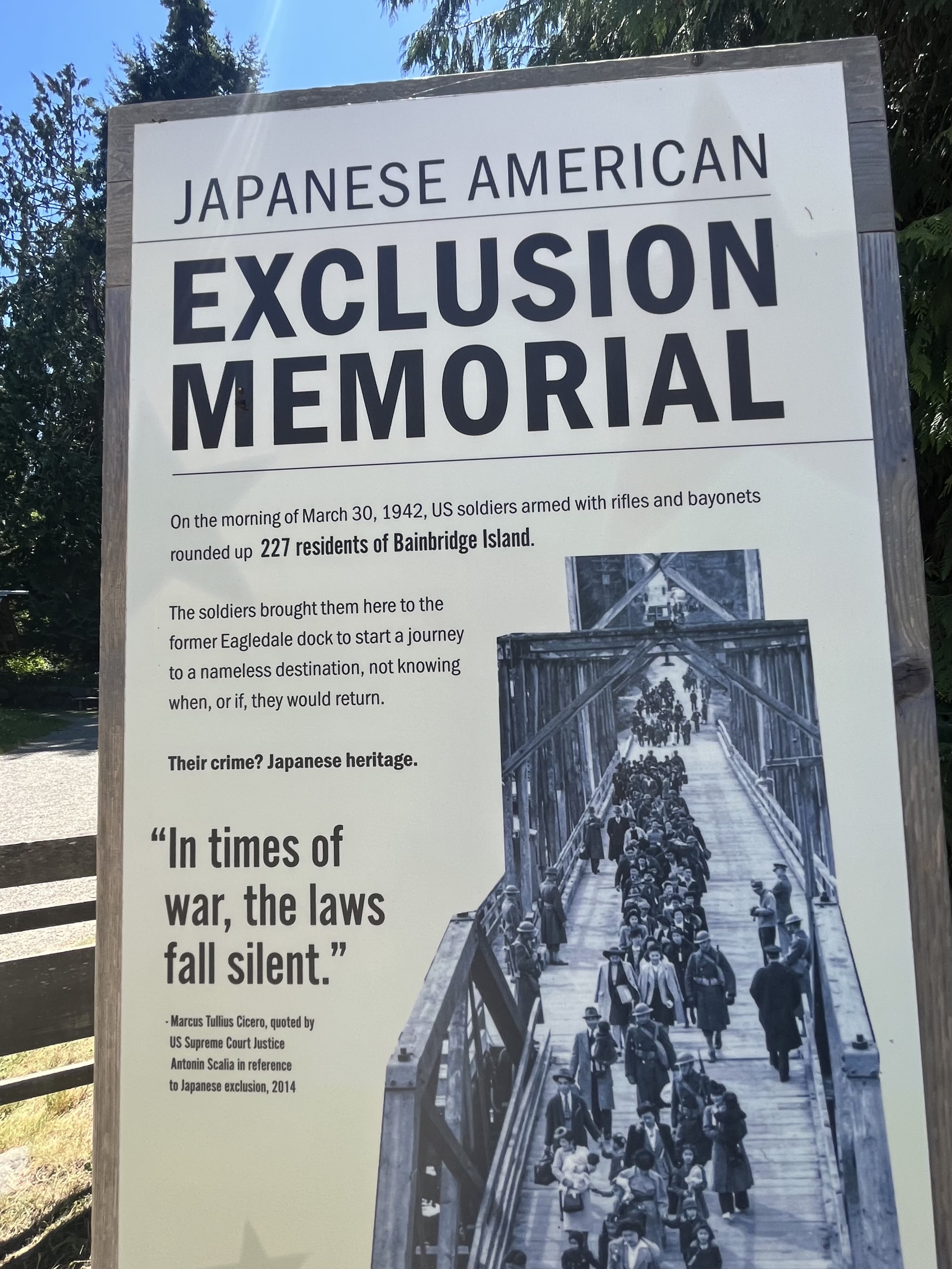

The Japanese American community grew and thrived in the Bainbridge Island community. But when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the lives of 125,000 West Coast Japanese Americans, including the 276 that lived on Bainbridge Island, were jeopardized as they were accused of being the “enemy” because of their Japanese heritage. Though 2/3rds of the Japanese Americans were US born citizens, on March 30, 1942, the Bainbridge Island residents were forced to leave their homes and businesses at the historic Eagledale Ferry dock, escorted by military carrying bayonets, to an unknown destination and future.

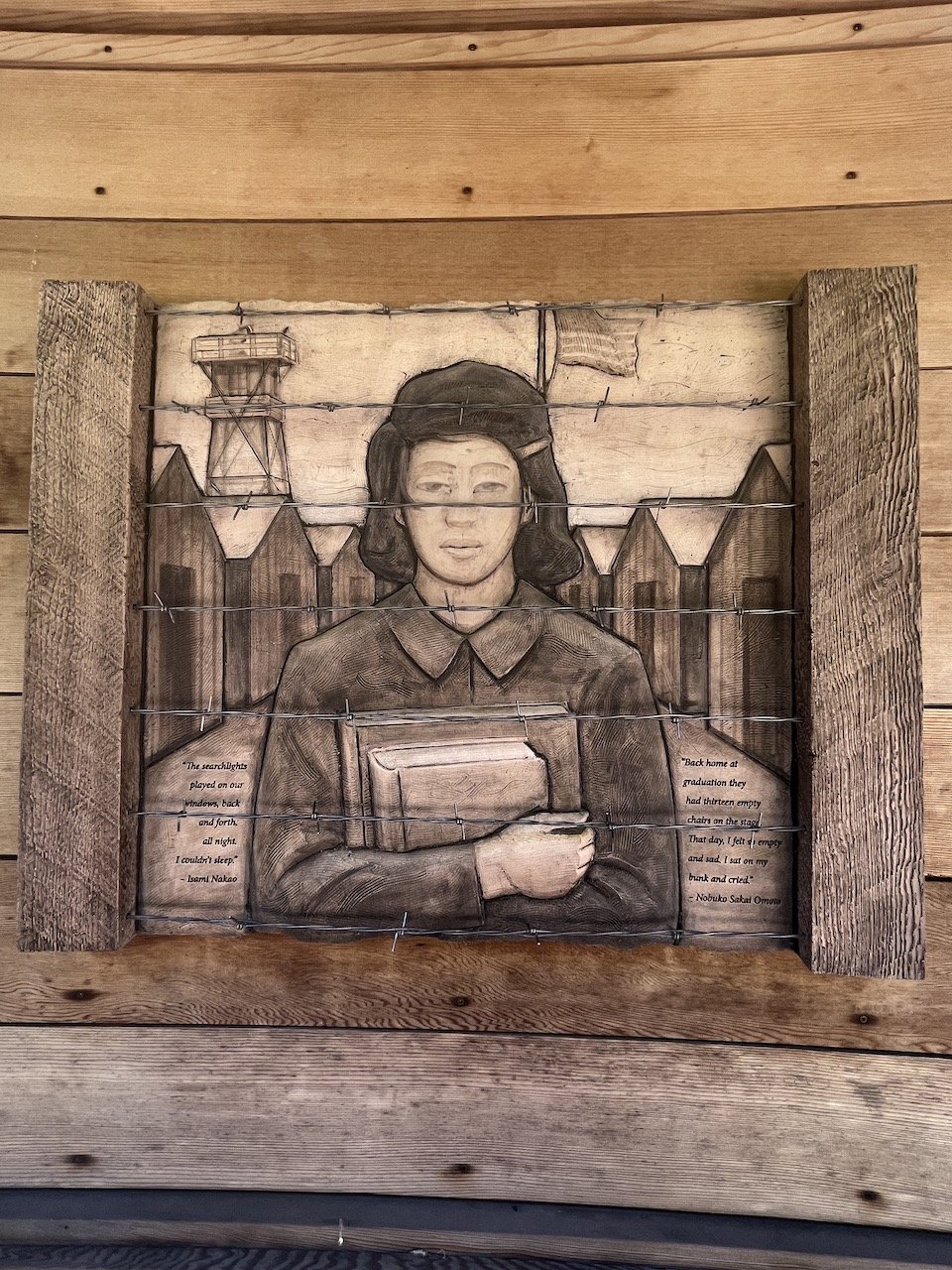

Given only 6 days before being removed by presidential executive order #9066, the Bainbridge Island families packed a single suitcase each and left their lives behind at this ferry dock location. This memorial, located in the midst of Pritchard Park, lists all 276 names and their ages on a 276 foot long path with a beautifully crafted wood and stone wall, one foot for every name. This path is the actual path the families took to the dock that took them away to the incarceration camp in 1942. Individual stories and terra cotta plagues tell poignant remembrances of this experience by the survivors. Down by the water’s edge, the Eagledale Ferry dock is framed with metal cutouts of soldiers holding bayonets as they “escorted” the innocent Japanese Americans from their Bainbridge Island home.

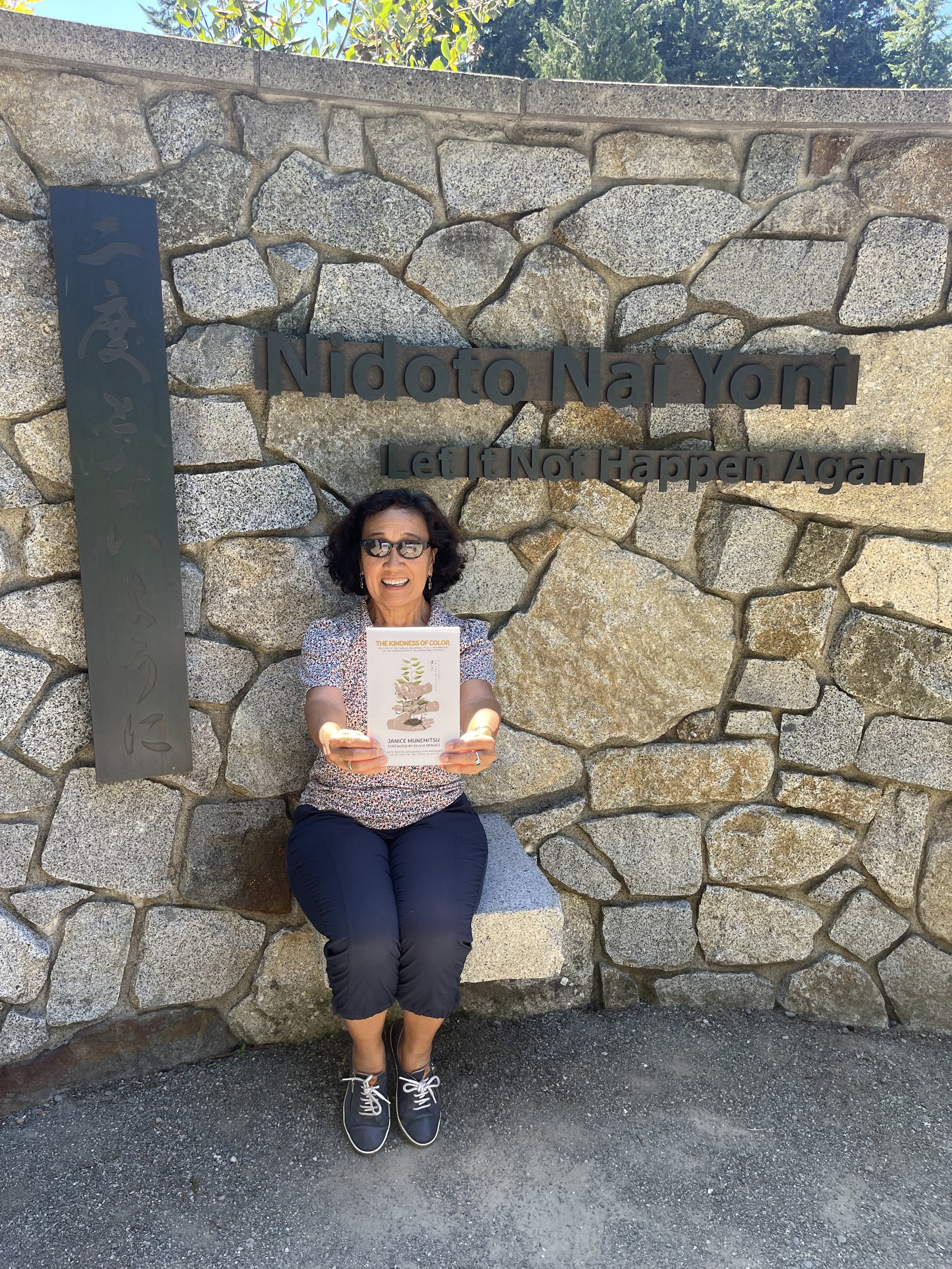

This was my first visit to the Bainbridge Memorial, but some of the stories shared aligned with my family’s experience. Amidst the harsh reality of being unfairly accused and sentenced to incarceration camps, these stories also carried a familiar theme of kindness by the community.

“Kindness is… omoiyari, sympathy and compassion shown and demonstrated for others.” (pg.79 “The Kindness of Color”)

Thirteen of those forced to leave were graduating seniors from Bainbridge High School. On graduation day 1942, there were 13 empty chairs on the stage in remembrance of these beloved Japanese American students, These graduates in absentia ended up spending their graduation day behind barbed wire, 800 miles south in hot and dusty Manzanar CA Incarceration camp, their hopes for their future now gravely uncertain.

While the caucasian neighbors didn’t find a way to stop FDR’s presidential executive order #9066, some did show kindness to their Japanese American neighbors, now incarcerated as suspected enemy spies for Japan. The owners of the Bainbridge Review newspaper sent news from home to their friends incarcerated and tried to keep communication between the community going, though they were now physically separated by hundreds of miles.

After the war, there was more uncertainty about what kind of homecoming they might receive. Many chose to relocate away from the west coast, especially if they had no home to go back to. Some lost their homes because they were unable to pay back property taxes while incarcerated or due to unscrupulous people who took advantage of their plight.

More than half of the Bainbridge Japanese Americans came back to the Island and many were met with kindness. A Quaker church helped the Takamoto family by coming to help them clean up their home and farm, getting it ready to replant and start farming again. Hjalmer Anderson helped the Harui family by paying the back taxes on the property so it would not be confiscated by the government. This property still exists as Bainbridge Gardens and Nursery, now operated by the Harui family descendents. The Raber family purchased the Koura farm, their neighbors farm, for one dollar in 1942, and sold it back to them for one dollar in 1945 upon their return.

I highly recommend everyone visit the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial (bijaema.org). It is a unit of Minidoka National Historic Site, the Idaho incarceration camp where the Bainbridge Island residents spent most of WWII after a short term at Manzanar.

Just a short ferry ride from Seattle and a nice neighborhood walk, you can find the memorial in Pritchard Park where a small National Park Service exhibit provides interpretive material. There is no admission fee and it's beautifully nestled in a fir and cedar tree forest.

The key message of the memorial is “Nidoto Nai Yoni” or “Let it Not Happen Again.” All of American history must be known, however difficult, so that we learn from our mistakes and prevent this from happening again to any innocent American citizen or legal resident. I hope we also learn that it's the kindness of each of us, as neighbors, to support each other in the midst of adversity. Let’s cultivate kindness and value each other as neighbors and friends!

This is the most beautiful tribute to a horrible part of our US history that I have seen and shows that beauty can arise from ashes, especially when we show kindness and “omoiyari” to one another.