Open Eyes, Open Hearts!

“When I open my eyes, it hurts,” I said, when someone asked me about my eye disease treatment. I was diagnosed with a rare disease called neurotrophic keratitis (NK - impaired nerves of the cornea) after a rapid, unexpected change in my vision. Blessed to have specialists nearby, and though rare, there is a cure for this. Only 65,000 Americans get this disease, so I was grateful for a cure that has an 80% effective cure rate vs. the total loss of vision. Oxervate was prescribed; I got started in mid January. The cure became my new hobby as it must be refrigerated and carefully handled for application in my eyes every 2 hours, 6 times a day for 8 weeks. Side effects are eye pain, light sensitivity, etc. which didn’t thoroughly describe the stinging or bruised feeling of my eye balls, or the tremendous light sensitivity that results while the nerves of the cornea are regenerated. “No pain, no gain” has been my 8 week motto, but it was hard to manage normal life these past 8 weeks.

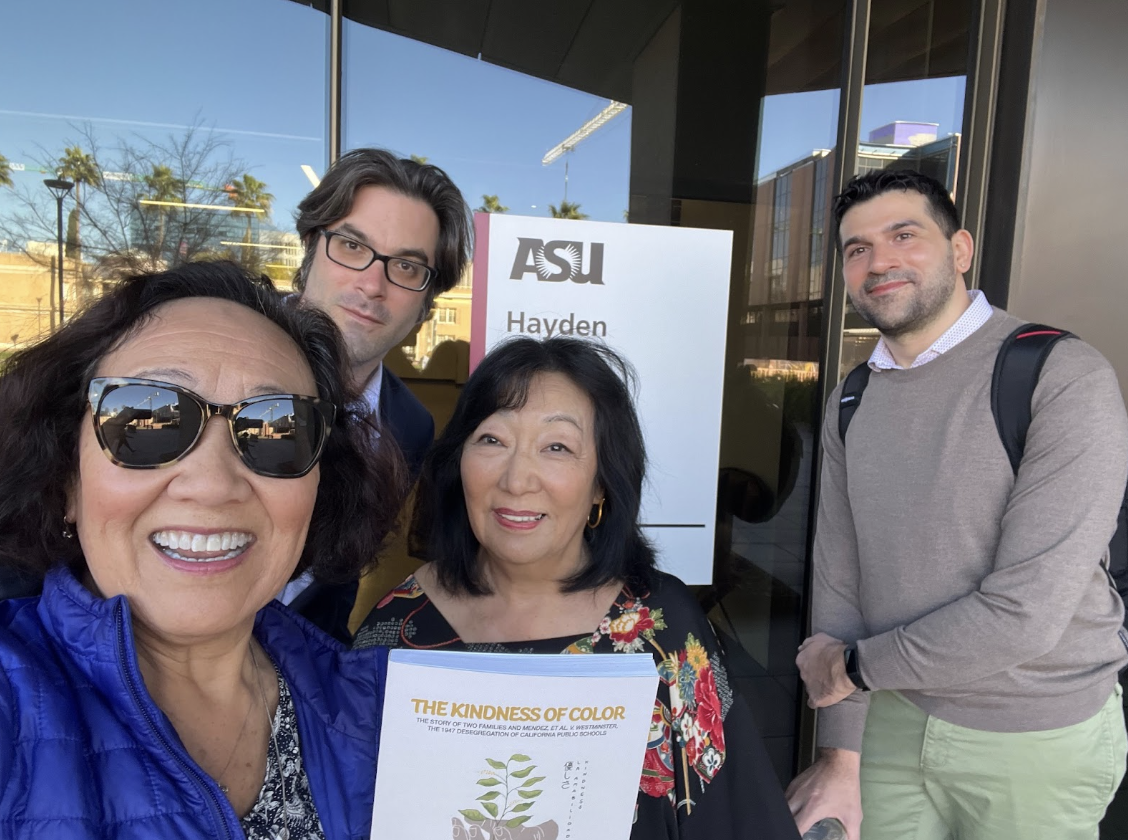

That was how my physical eyes felt, but it wasn’t going to stop me from traveling to ASU in Tempe, AZ to speak at the 2 day program, “The Incarceration of Japanese Americans in Arizona: Perspectives, Reflections, and Afterlives.” Organized by Dr. Daniele Lauro, Asst. Professor of Asian History, and Dr. William Hedberg, Assoc. Professor of Japanese, the program included screenings of two documentaries, “And Then They Came for Us,” and “For the Sake of the Children.”

Our audience was a blend of students, faculty, and “life long learners” from the community - all came with a sincere desire to learn and many really had a good knowledge of the Japanese American WWII incarceration.

One of the topics that comes up is the largely unspoken history by many of the surviving incarcerees and the emotional trauma on the Japanese American community at large. While my family told me about “camp” during WWII, they did not dwell on the loss of freedom for 3 ½ years or the financial hardship and loss, and no word was said of the emotional trauma at all. After all, they had a farm to come home to while many others had no place to return. Perhaps time heals these wounds, but I know the trauma was still there. When 9/11 happened, my mother and aunt were very fearful that they would be taken away again. “What if they come and you are not here?” was the direct quote to me. The rhetoric on the news 24/7 was so familiar to them, only at 9/11 it was targeted at those of Middle Eastern descent. My mother and aunt went into delayed PTSD after 60 years.

There is no right or wrong about whether families talked about this time in their personal history or not, yet so many family descendents have told me that they better understand their family histories after reading “The Kindness of Color.” I’m quick to tell them that ours is one of 125,000+ stories, and their family story will be uniquely theirs, but many of the facts are the same. So many surviving Japanese Americans have NEVER told their families about their incarceration. NEVER. And there is a longing from their children, grandchildren, and extended family to know their truth and personal history of survival in the midst of extreme adversity.

“When I open my eyes, it hurts.“ Not just physically, but there is so much unspoken pain in the incarceration history. In the midst of the panel discussion, these words echoed back in my mind. Difficult history left untold. Painful memories left unspoken. Trauma and emotional fractures left unprocessed. It’s too painful to open eyes to the truth of what was suffered, endured, or lost for those 3-4 years in the midst of America’s desert wastelands. It’s too painful to let your family see what you endured - not just physically but emotionally - the disgrace of being unjustly convicted, without evidence of being disloyal to the only country you know. All because your name and skin color resembled the WWII enemy Japan.

And I know that for some, like my mother and aunt, they didn’t even have words to express their feelings of trauma, especially when their mother, my grandmother, died at the incarceration camp’s make-shift “clinic hospital” eight months after the barbed wire gates shut behind her.

The more I hear about so many Japanese American descendents never hearing these stories from their families, and other Americans either never yet hearing about this, or knowing any details of Japanese Americans in “camps” in WWII, the more I feel this is a God-given mission for me to share our story for healing. When I first was urged to write my book, I had no idea that people would be interested in this history. But now, I realize that for many, it has become part of their journey toward healing as we must “know the truth and the truth will set you free.”

After the program, I had some time before my flight, so I explored ASU’s campus of unique architecture, solar panels creating shade even for the southwestern cactus landscape, and the sand stone colored campus landmarks. And somewhere it said there was a campus art gallery…

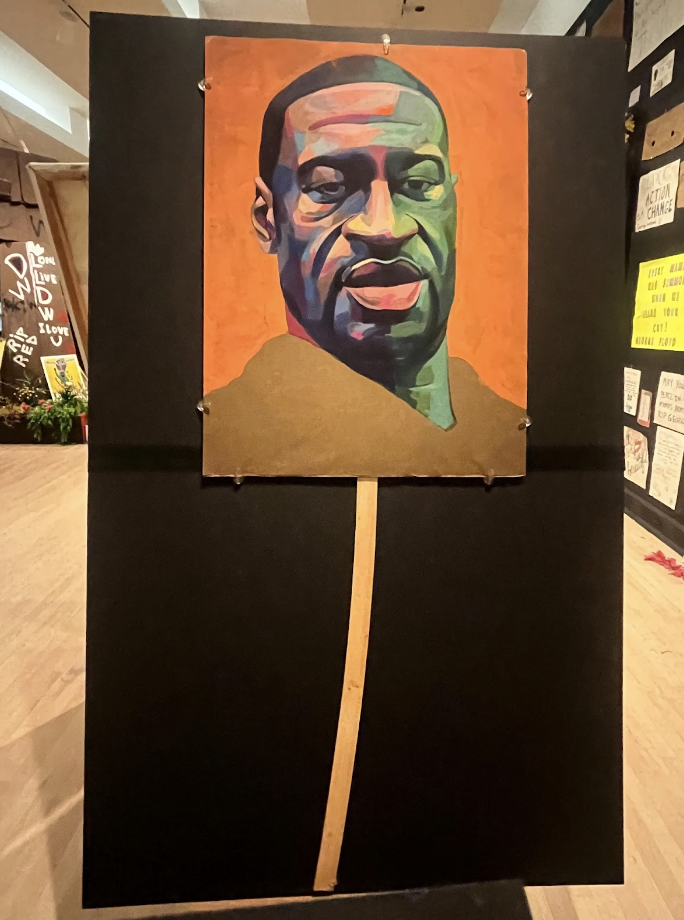

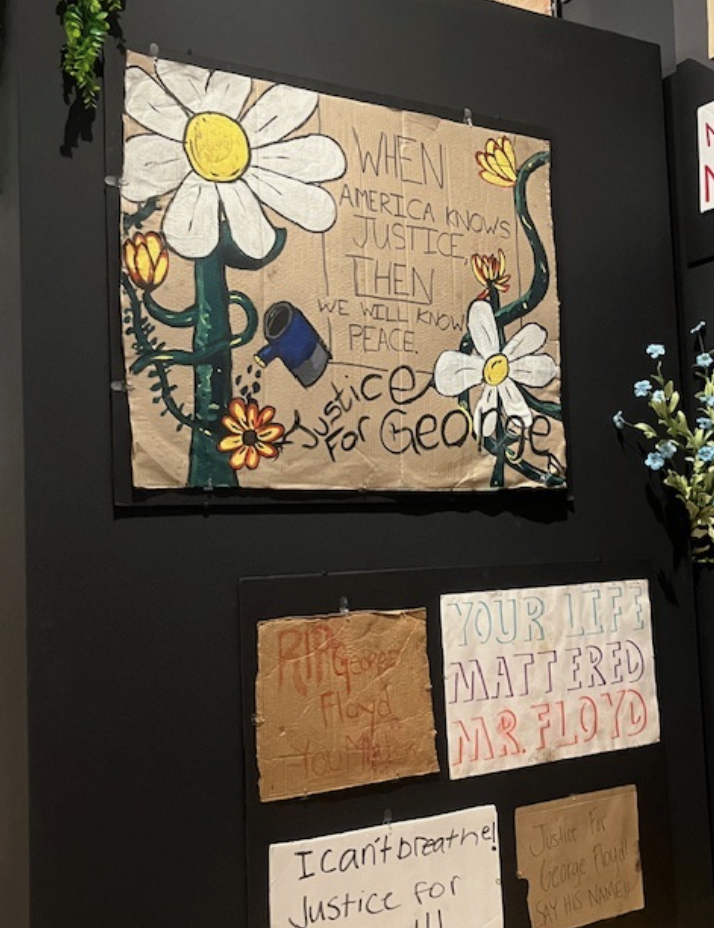

“Twin Flames: The George Floyd Uprising from Minneapolis to Phoenix” was the major exhibit, a partnership with ASU’s Center for Work and Democracy and the George Floyd Global Memorial. Presented for the first time outside of Minnesota, I thought again…

“When I open my eyes, it hurts… my heart.” This was a community-led collection of individually-created memorials left at the scene of George Floyd’s death, now known as George Floyd Square in Minneapolis. Mourners expressed their grief in words and art. Powerful words. Powerful Art.

“We are Not Free Until We are All Free.”

“When American Knows Justice, then We Will Know Peace.”

“Racial Trauma Runs Deep, But Together We Rise.”

“Remember. Reclaim. Reconnect. This is a Healing Place.”

“When I open my eyes, it hurts… my soul.” As I viewed the exhibit, it brought back the reality of hatred against one another. Seeing the mourners’ emotion and grief took this from something I’d seen on TV to the reality of a real Black American life lost too soon, loved ones mourning, and the injustice and hatred that led to the murder of George Floyd.

But the mourner’s art also displayed hope and moving forward together. Some of the words on the hand-made posters are as true today - for all people discriminated against and traumatized because of the color of their skin or country of origin. And they echoed true for the 1940s Japanese American history I just spent time speaking of.

“When I open my eyes, it hurts, but WE....” Significantly, the key to these posters is the word WE. Together We Rise. Not Free until WE are all Free. We will know Peace. And Together, this can be a Healing Place for Us.

“Kindness is…standing up for those being oppressed because we are one human race.” (pg. 147)

“Kindness is…looking beyond your own race in order to look out for others as well.” (pg.150)

“Kindness is…respecting people for who they are and not judging them by the color of their skin.” (pg. 184”

“When I open my eyes, it hurt…physically for about 8 weeks. But week 8, the last of the treatment, the pain began to subside. The cornea specialist announced that it worked! My eyesight is much improved, the pain is decreasing, and I am one of the 80% cured of NK! Praise God!

But I will long remember the analogy to keeping my eyes open to notice and respond to the pain of others, even when it hurts. I will remember to try to always be one of many healing places combating hatred and trauma. We all need more healing places and spaces in life - will join me in offering hope and healing to those around us?

Together, Let’s “Remember, Reclaim, Reconnect. This is a Healing Place.”